694 views

Dakshinamurthy B et al.: Fascioliasis – Pleuropulmonary Manifestations an Overview

Fascioliasis – Pleuropulmonary Manifestations an Overview

Dakshinamurthy B1, Ajay Narasimhan2, Narasimhan R3

1Post Graduate, 3Senior Consultant, Dept of Respiratory Medicine, Apollo Hospitals, Chennai

2Consultant, Dept of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Apollo Hospitals, Chennai

Abstract

Fascioliasis, which is a zoonotic infestation caused by the trematode Fasciolia hepatica (liver fluke), is primarily a disease of herbivorous animals such as sheep and cattle. Humans become accidental hosts through ingesting uncooked aquatic plants such as watercress.

It presents a wide spectrum of clinical pictures ranging from fever, eosinophilia and vague gastrointestinal symptoms in the acute phase to cholangitis, cholecystitis, biliary obstruction, extrahepatic infestation, or asymptomatic eosinophilia in the chronic phase. Because of its infrequent and protean presentation and the lack of clinical data, the management of acute infection is challenging. Lung manifestations of fasciolia are very rarely reported in the literature. This article reviews the pleuropulmonary complications of fasciolia hepatica infection in humans.

Corresponding Author: Dr.Dakshinamurthy B, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Apollo Main Hospitals, 21, Greams Lane, Off Greams Road, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India.

How to cite this article: Dakshinamurthy B, Ajay Narasimhan , Narasimhan R, Fascioliasis – Pleuropulmonary Manifestation an Overview, JAPT 2019: 2(2):55-60

Introduction

Fascioliasis is a cosmopolitan parasitic zoonosis produced by the trematode Fasciolia hepatica in its adult stage that affects herbivorous mammals (cattle, goats, and sheep) and occasionally human beings as incidental hosts1.

Fasciolia hepatica is a non-segmented flat hermaphrodite trematode, measuring 2-3 cm long by 10-13 mm wide2. Human beings are infected by consuming aquatic vegetables contaminated with metacercarias (larval form encysted and resting), particularly wild watercress (nasturdium officinale), besides mint, alfalfa, reeds, lettuce and spinach. Other sources of infection are: ingesting badly cooked liver of infected animals and, on a lesser scale, drinking contaminated water.

The biological cycle can be in one of two forms:

A. Sexual: which occurs in the definitive host (ruminants, other animals and humans).

B. Asexual: which takes place in the intermediary host (molluscs of the genera fossarea and lymnaea)3, 4.

Larvae come out of the cyst in the duodenum to penetrate through the intestinal wall and reach the peritoneum. Larvae proceed to the liver capsule and parenchyma and ultimately to the bile ducts5,6.

Parasites may rarely locate ectopically in the lungs, skin, heart, brain, stomach, eyes andlymph nodes through hematologic, lymphatic route or direct invasion7-12. On the other hand, even without a parasite localized in chest cavity, pulmonary abnormalities such as infiltrates and pleural effusions (atypical lung involvement) may occur indirectly through parasitic infection, especially in acute fascioliasis.

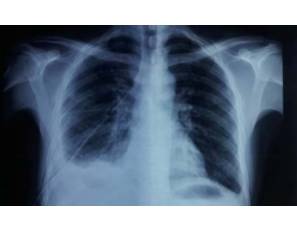

When we reviewed the literature, we did not encounter publications, except a few case reports, regarding lung involvement of FH13-16. Indeed, because FH is localized in the liver, signs and symptoms associated with the disease of this organ are forefront. Therefore, the findings associated with lung and other organs may be ignored by clinicians. Therefore, lung abnormalities associated with FH are not investigated with chest radiography in routine clinical practice. In our institute we came across an interesting scenario wherein the patient is a 35 year old male from Assam, a farmer by occupation presented with complaints of fever, cough with minimal expectoration and breathlessness for 3 months duration. He also had an associated right sided chest pain for the past 3 months and loss of weight of around 5 kgs in the same period. He denied prior history of anti-tuberculous treatment and was a non-smoker and an occasional alcohol user. He was evaluated elsewhere for the same complaints and found to have a right sided pleural effusion and came to our centre for further management. His chest X-ray revealed a right sided moderate pleural effusion and CT chest was also done that showed large right sided pleural effusion with fissural extension and pleural thickening, with patchy right lower lobe consolidation , calcified enlarged mediastinal lymphnodes and an evolving abscess in the superior aspect of segment 8 of liver.

Pleural fluid aspiration was done which on cytology showed sheets of eosinophils, was negative for malignant cells and negative for AFB smear and GeneXpert for MTB complex. His blood investigations were normal except for increased ESR and peripheral eosinophilia of 35% eosinophils in the differential counts. Fibre optic Bronchoscopy was done that was normal study and negative for GeneXpert for MTB complex.

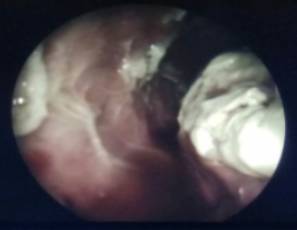

Fig 1 – Thorascopic Image Showing Visceral and Parietal

Pleural Nodules and Adhesions

Fig 2 : Right Pleural Effusion with ICD in SITU

Hence we proceeded with rigid thoracoscopy which revealed multisepated pleural effusion with lots of adhesions and multiple nodules in the parietal and visceral pleura [FIG 1] Intercostal drainage tube was placed in situ [FIG 2]. Biopsy of the pleura showed fibroblastic proliferation with intense eosinophilia suggestive of eosinophilic pleuritis. Hematologist opinion was also sought wherein which a bone marrow aspiration cytology showed trilineage haematopoiesis, normoblastic maturation, eosinophilia and plasmacytosis and increased iron stores. Bone marrow trephine biopsy showed mildly hyper cellular marrow with eosinophilia, mild plasmacytosis and increased iron stores. Moving ahead we proceeded with Contrast CT of the abdomen that showed branching linear tracts over the surface of liver into the substance of liver on both the lobes very much suggestive of FASCIOLIA HEPATICA [FIG 3] infection involving the right pleura, liver and also the lower pole of the right kidney. The patient was started on T.Nitazoxanide 500 mg thrice daily for 2 weeks and the Intercostal tube was removed after the lung expanded adequately and drain was minimal.

FIG 3 : Fasciolia Tunnel Sign – Linear Tracts Over the Liver Surface

Going retrospectively we enquired his eating habits and found that he used to take fresh raw uncooked vegetable salad grown from his kitchen backyard and also had the habit of drinking liquor with fresh water fish dipped in it and reciprocally the scenario was like we had to “fish out the fasciolia from the pleural wine”.

Around 7% of the pleural effusion are eosinophilic in nature with more than 10% of eosinophils in the differential counts 17,18. Mostly the pleural fluid eosinophilia is due to either air or blood in the pleural space. The factor responsible for the increased colony-forming activity of eosinophils and their increased survival appears to be IL-5 19,20, although IL-3 and granulocyte or macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) may also play a role (19). The source of the IL-5 appears to be the CD4 lymphocyte in the pleural fluid (20), but the eosinophils in the pleural fluid may themselves also produce IL-5 (19). The source of the eosinophils in eosinophilic pleural effusions appears to be the bone marrow; no progenitor cells are present in the pleural space. The most common cause of pleural fluid eosinophilia is air in the pleural space. In a series of 127 cases with more than 20% eosinophils in the pleural fluid, 81 (64%) were thought to have pleural fluid eosinophilia secondary to air in the pleural space (21).The second most common cause of pleural fluid eosinophilia is blood in the pleural space. Following traumatic hemothorax, pleural fluid eosinophils do not usually become numerous until the second week (21). There is frequently an associated peripheral blood eosinophilia that does not disappear until the pleural effusion is completely resolved (22). The pleural effusions associated with pulmonary embolization are frequently bloody and contain numerous eosinophils (23). Bloody pleural fluids due to malignant disease are not usually characterized by eosinophilia (21) Kalomenidis and Light (24) reviewed the etiology of 392 cases of eosinophilic pleural effusions when cases associated with pleural air and/or blood were excluded. They reported that the most common diagnosis was idiopathic (39.8%), followed by malignancy (17%), parapneumonic (12.5%), transudates (7.9%), tuberculosis (5.6%), pulmonary embolism (4.3%), and others (12.8%). In a recent study of 13 5 patients with eosinophilic pleural effusions from a single institution, the following diseases were responsible: malignancy 34.8%, infections 19.2%, unknown 14.1%, posttraumatic 8.9%, and miscellaneous 23.0% (17). Pleural eosinophilia is common in patients with asbestos-related pleural effusions. Patients with eosinophilic pneumonia frequently have pleural effusions and the mean eosinophil percentage in the pleural fluid was 38% in one study (25). The pleural effusions secondary to drug reactions are frequently eosinophilic. Offending drugs include dantrolene, bromocriptine, and nitro-furantoin. Pleural effusions secondary to parasitic diseases such as paragonimiasis (26), hydatid disease (27), amebiasis (21), or ascariasis (21) frequently contain a large percentage of eosinophils. Lastly, the pleural effusion associated with the Churg-Strauss syndrome is also eosinophilic (28).

Acute fascioliasis refers to the initial, hepatic phase of the parasitic disease. It is characterized by tissue destruction caused by the migration of the immature parasites from the small intestine to the biliary system. Because of its invasive nature, the acute stage of fascioliasis causes far more morbidity than chronic infection when adult worms inhabit the biliary tree. However, as for other neglected diseases, comprehensive clinical studies are lacking, and the most convincing clinical data derive from small retrospective case series or single case reports [29-32]. The typical clinical spectrum of acute fascioliasis encompasses anorexia (sometimes associated with nausea and vomiting), which might lead to weight loss, abdominal pain, especially in the upper abdomen, tender hepatomegalia, night sweats, fever, and other immunemediated manifestations, such as urticaria or arthralgias. Other, less frequently reported, findings include splenomegalia, ascites, subcapsular hepatic haematoma, intra-abdominal haemorrhage, pleural or pericardial effusion, and respiratory symptoms [33,31,34]. Ectopic larvae in other localizations, such as subcutaneous tissue, eyes, and the central nervous system,may cause a variety of other clinical manifestations31. The leading laboratory abnormality is hypereosinophilia; hypergammaglobulinaemia and anaemia might also be present35. The incubation period ranges from a few days to several weeks; the acute stage of fascioliasis usually lasts for 2–4 months33.

Patients with respiratory symptoms in the foreground are evaluated as atypical fascioliasis (31). Cough, hemoptysis and chest pain may be seen in these patients (36). Some patients have eosinophilrich sputum discharge and dyspnea and they are erroneously treated as asthma (37, 38). In various studies, complaint of cough was found as 14%, 15% and 33% in the acute phase (31, 39, 40). Arigona et al. reported chest pain and dyspnea in 3 out of 20 fascioliasis patients (31). In another study, respiratory symptoms were detected in 10 patients (17.9%) and three patients with lung involvement belonged to this group (41). They detected cough in 14.2% patients, dyspnea in 12.5%, chest pain in 8.9% and sputum in 3.6%. Co-existence of cough, dyspnea and chest pain in two out of three patients is striking. Simultaneous chest radiographs were not obtained in other studies, thus lung involvement or presence of primary pulmonary disease that may have been a component of fascioliasis could not be evaluated. Pulmonary signs and symptoms are considered to be related with hepatic destruction caused by larvae and inflammatory response. The severity of symptoms has been reported to vary according to number of parasites, location, immune response of host against parasite and especially eosinophil level(31) . Larvae were reported to ectopically locate in the lungs, skin, heart, brain, stomach, epididymis, eyes and lymph nodes(7-12). Ectopic fascioliasis appears as masses and abscesses with eosinophilic and mononuclear infiltrations develop due to tissue injury in these organs(21). How parasites migrate to ectopic tissues is not known. However, different theories suggest that migration may occur through hematogenous, lymphatic or direct route(22,23). Presence of larvae in the thorax may only be detected with thoracoscopy and biopsies and these procedures are not recommended for definite diagnosis due to their invasive nature. Physical examination findings of the lungs vary according to the pathology caused by FH.

Usually the rales are presence when cough is in the foreground. Dullness on percussion, is detected when a pleural effusion develops and a tympanic sound is detected in the presence of a pneumothorax. A decrease is detected in respiratory sounds on auscultation. Bronchial sounds and rales may be heard when infiltration and consolidation develop. Lung involvement may be seen in different forms in radiologic evaluation. Loeffler syndrome like displacing parenchymal infiltrates and pleural effusion are the most common radiological findings (13). However, publications are available reporting pneumothorax development (16). Routine laboratory test results of the patients who developed lung abnormalities (white blood count, ESR, ALT, AST, ALP and bilirubin levels) were similar to those of the patients without lung abnormality. An eosinophilic reaction may be shown in the fluid obtained in presence of pleural effusion and pericarditis (31).

Hepatic imaging is crucial in patients with possible acute fascioliasis. In concordance with other published data29,30,31, abdominal ultrasound did not contribute to the diagnosis of acute fascioliasis. However, this technique is of value in chronic fascioliasis, when adult worms inhabit the biliary tract, causing inflammation and/or dilatation, and might be seen as mobile structures in the gall bladder or choledochus45. A useful imaging technique is CT, which reveals hypodense focal lesions that might be confused with metastasis or abscess; more typical for acute fascioliasis are hypodense tunnel-like lesions, (fasciolia tunnel sign ) which, over time, slowly change in a centripetal manner32. Magnetic resonance imaging, which offers no diagnostic advantage, is characterized by hypointense lesions in T1- weighted images, and hyperintense signals in T2 images35. Periportal lymph nodes are not infrequent but are non-specific. The combination of upper abdominal pain, marked eosinophilia and hypodense lesion in CT imaging is highly indicative of acute fascioliasis35. Other rare causes of this combination of findings include hepatic toxocariasis and hepatic capillariasis.

The easiest means of establishing the diagnosis is visualization/demonstration of ova in the stool (2), but it has low sensitivity. Because of no ova release in the stool in the acute phase and intermittent ova release in the chronic phase of the disease, serological tests may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Triclabendazole is the current treatment of choice for fascioliasis but unfortunately the drug is not available in india. It is administered at a dose of 10 mg/kg/day either once or twice over two consecutive days. The other alternative drug is T nitazoxanide 500 mg twice daily for 2 weeks.

Conclusion

The Fasciolia hepatica transmission chain is well documented with 70% of infections related to the consumption of watercress by persons living in the high risk areas. Consequently, when undertaking the clinical evaluation of patients from these high risk areas with abdominal pain and eosinophilia, one should consider the possibility of a Fasciolia hepatica infection and, for the clinical evaluation, include questions of the patient’s food consumption habits as well as performing the relevant faeces tests and Fasciolia hepatica tests. Fascioliasis should be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis and treatment of patients with respiratory symptoms and eosinophilia. Once the presence of Fasciolia hepatica infection has been established and successfully treated, then it is also important to ensure long term follow-up checks to control for any possible long term effects, possibly irreversible, that could have arisen from the Fasciolia hepatica infection

References

1. Atias A, Neghme A (1991) Fascioliasis in Parasitología Clínica. Publication’s Tecnicas Mediterráneo, Santiago, Chile, pp. 334-340.

2. Berenguer J Mosby/Doyma Libros. (2nd Edn), Elsevier SA, Netherlands. pp. 800-802.

3. Alban M, Jave J, Quisipe T (2002) Fascioliasis en Cajamarca. Revista de Gastroenterología del Perú 22 pp. 28-32.

4. López M, Huerto L, Hernandéz S, Acuña A, Nari A (1996) Fasciolosis en la Republica Oriental de Uruguay 12: 37-43. 5.

5. King CH. Flukes (liver, lung and intestinal). In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, StantonBF (eds). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics (18th ed). Philadelphia: WB Saunders Elsevier, 2007: 1510-1511.

6. Aksoy DY, Kerimoğlu U, Oto A and et al. Infection with fasciolia hepatica. Clin Microbiol Infect 2005; 11: 859-61.

7. Zali MR, Ghaziani T , Shahraz S and et al. Liver, spleen, pancreas and kidney involvement by human fascioliasis: imaging findings. BMC Gastroenterology 2004; 4: 15.

8. Basarali MK, Kaplan I, Cicek M and Cakir F. The relationship between trace elements and ceruloplasmin with severity of fascioliasis patients. ActaMedicaMediterranea, 2013, 29: 177- 81.

9. Pulpeiro JR, Armesto V, Varela J and et al: Fascioliasis: findings in 15 patients. Br J Radiol 1991; 64: 798-801. 10. Öngören AU, Ozkan AT, Demirel AH and et al. Ectopic intraabdominal fascioliasis. Turk J Med Sci 2009; 39: 819-23.

11. Xuan LT, Thien Hun N, Waikagul J. Cutaneous fascioliasis: a case report in Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005; 72: 508-9.

12. Cheng AC, Zakhidov BO, Babadjonova LJ and et al. A 6- year old boy with facial swelling and monocular blindness. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45: 1238-9.

13. Aliaga L, Díaz M, Quiroga J and et al. Eosinophilic pulmonary disease caused by Fasciolia hepatica. Description of a case and review of the literature. Med Clin (Barc) 1984; 82: 764- 7.

14. Corredoira JC, Pérez R, Casariego E and et al. Eosinophilic pleural effusion caused by Fasciolia hepatica. EnfermInfeccMicrobiolClin 1990; 8: 258-9.

15. Ibáñez de Maeztu JC, Aguirrebengoa K, Montejo M and et al. Pleural effusion associated with acute hepatic fascioliasis. EnfermInfeccMicrobiolClin 1994; 12: 320-1.

16. Aghajanzadeh M, Sarshad A, Ebrahimian R. Pneumothorax a rarity in fascioliasis. w w w . a m s . a c . i r / A I M /9924/aghajanzadeh9924.html

17. Krenke R, Nasilowski J, Korczynski P, et al. Incidence and etiology of eosinophilic pleural effusion. Eur Respir J 2009; 34:1111-1117.

18. Ferreiro L, San Jose E, Gonzalez-Barcala FJ, et al. Eosinophilic pleural effusion: incidence, etiology and prognostic significance. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47;504- 509.

19. Nakamura Y, Ozaki T, Kamei T, et al. Factors chat stimulate the proliferation and survival of eosinophils in eosinophilic pleural effusion: relationship co granulocytemacrophage colony-stimulating factor, interleukin-5, and interleukin-3. Am J Respir Cell Mo! Biol. 1993;8:605-611

20. Schandene L, Namias B, Crusiaux A, et al. IL-5 in posttraumatic eosinophilic pleural effusion. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;93:115-119.

21. Spriggs AI, Boddingcon MM. The Cytology of Effesions, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Grune& Scraccon;l968

22. Maltais F, Laberge F, Cormier Y. Blood hypereosinophilia in the course of post-traumatic pleural effusion. Chest. 1990; 98:348-351.

23. Romero Candeira S, Hernandez Blasco L, Soler MJ, et al. Biochemical and cycologic characteristics of pleural effusions secondary co pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2002;121:465-469.

24. Kalomenidis I, Light RW. Eosinophilic pleural effusions. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2003;9:254-260.

25. Philit F, Etienne-Mastroianni B, Parrot A, et al. Idiopathic acute eosinophilic pneumonia: a study of 22 patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1235-1239.

26. Klein A, Talvani A, Cara DC, et al. Stem cell factor plays a major role in the recruitment of eosinophils in allergic pleurisy in mice via the production of leukotriene B 4′ J Immunol. 2000; 164:4271-4276

27. Yacoubian HD. Thoracic problems associated with hydatid cyst of the dome of the liver. Surgery. 1976;79:544-548

28. Erzurum SE, Underwood GA, Hamilos DL, et al. Pleural effusion in Churg-Strauss syndrome. Chest. 1989;95: 1357- 1359.

29. Graham CS, Brodie SB, Weller PF. Imported Fasciolia hepatica infection in the United States and treatment with triclabendazole. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33: 1–5.

30. Noyer CM, Coyle CM, Werner C, Dupouy-Camet J, Tanowitz HB, Wittner M. Hypereosinophilia and liver mass in an immigrant. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2002; 66: 774– 776.

31. Arjona R, Riancho JA, Aguado JM, Salesa R, Gonza´lezMarcı´as J. Fascioliasis in developed countries: a review of classic and aberrant forms of the disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 1995; 74: 13–23.

32. Marcos LA, Tagle M, Terashima A et al. Natural history, clinicoradiologic correlates, and response to triclabendazole in acute massive fascioliasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008; 78: 222–227.

33. World Health Organization. Report of the WHO Informal Meeting on use of triclabendazole in fascioliasis control. Geneva: WHO, 2007.

34. MacLean JD, Cross J, Mahanty S. Liver, lung and intestinal fluke infections. In: Guerrant RL, Walker DH, Weller PF, eds. Tropical infectious diseases: principles, pathogens & practise, 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingston Elsevier, 2005; 1349–1369.

35. Marcos LA, Terashima A, Gotuzzo E. Update on hepatobiliary flukes: fascioliasis, opisthorchiasis and clonorchiasis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2008; 21: 523–530.

36. Schussele A, Laperrouza C. Les distomatoses hepatiques: a propos de 9 observations person) Facey RV, Marsden PD: Fascioliasis in man: Anoutbreak in Hampshire. Br Med J 1960; 2: 619- 25

37. Tropical and Geographical Medicine. 2nd ed. New York: Mc Graw-Hill, 1990: 473-89.

38. Flores M, Merino J, Aguirre C: Pulmonary infiltrates as first sign of infection by Fasciolia hepatica.Eur J Respir Dis 1982; 63: 231-3.

39. Karahocagil.MK, Akdeniz H, Sünnetçioğlu M and et al. A familial outbreak of fascioliasis inEastern Anatolia: A report with review of literature. ActaTropica 2011; 118: 177-83.

40. Turhan O, Korkmaz M, Saba R and et al. Seroepidemiology of fascioliasis in the Antalyaregion and uselessness of eosinophil count as asurrogate marker and portable ultrasonographyfor epidemiological surveillance. Infez. Med 2006; 14: 208-12.

41. Cengizhan sezgi Pulmonary Findings In Patients With Fascioliasis .Acta Medica Mediterranea, 2013, 29: 841

42. Catchpole BN, Snow D. Human ectopic fascioliasis. Lancet 1952; 2: 711-12

43. Rushton B, Murray M. Intrahepatic vascular lesions in experimental and natural ovine fascioliasis.J Pathol 1978; 125: 11-6.

44. Neff GW, Dinavahi RV, Chase V and et al. Laparoscopic appearance of fasciolia hepaticainfection. GastrointestEndosc 2001; 53: 668-71.

45. Cosme A, Ojeda E, Cilla G et al. Fascioliasis hepatobiliar. Estudio de una serie de 37 pacientes. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001; 24: 375–380.